By Victor Greto

Innocence aged.

Not lost.

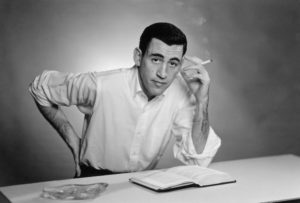

Believe it or not, it’s more than 70 years since J.D. Salinger published The Catcher in the Rye, America’s quintessential 20th-century novel of adolescent angst.

More than 60 million copies later, the book has helped shape many an American male’s sense of himself.

It’s a well-wrought, ironically bitter portrait of Holden Caulfield, a preppy adolescent thrust starkly into a world of cultural phonies, smothering adults and nasty fellow teens.

And it is peppered with Salinger’s vision of innocence, in the guise of Holden’s younger sister, Phoebe.

Holden’s dilemma is that of other Salinger fictional protagonists: Teetering on adulthood, they try not to grow up. Yet even as they do, they look lovingly back upon prepubescent children – girls – as a portal to a perennial youth without compromise and phonies and complexity.

Listen to Holden describing to his little sister what he wants to be at 16:

“I keep picturing all these little kids playing some game in this big field of rye and all. Thousands of little kids, and nobody’s around – nobody big, I mean – except me. And I’m standing on the edge of some crazy cliff. What I have to do, I have to catch everybody if they start to go over the cliff – I mean if they’re running and they don’t look where they’re going I have to come out from somewhere and catch them. That’s all I’d do all day. I’d just be the catcher in the rye and all. I know it’s crazy, but that’s the only thing I’d really like to be. I know it’s crazy.”

It sounds like the perfect job for another kid who didn’t want to grow up: Peter Pan.

At the end of the novel, Holden has a mental breakdown, seemingly unable to handle what he must inevitably become, an adult.

The novel is an ironic masterpiece – but many of us who read it and related to it during our adolescence never really understood its irony.

We read it sentimentally, even nostalgically, at face value, as though to say, yes, Holden’s right: Most people are phonies and pretentious, while I, like Holden, have more common sense and authenticity.

If allowed to grow, that adolescent attitude blossoms into adult self-righteousness.

But that attitude is not confined to individuals.

It has been one of the perennial inspirations for our culture, profoundly affecting our books, TV, movies and politics.

In other words, Holden’s cynical view of adults and our sentimental reaction to the book are confused examples of a greater phenomenon.

It’s part of the more than two-and-a-half-century-long intrinsic American belief in its own innocence.

The persistence of this quaint understanding of the world has unceremoniously jostled our great literature and art to the margins of the culture.

With the advent of mass media in the 20th century, and the proliferation of entertainment and, now, the ubiquity of social media echo chambers, it’s gotten much worse.

Much of our culture has become self-confessional, memoir-mad, hypnotized by its own aging reflection, much of it angry at either the world or parents who just never understood.

Our Reality TV puts wounded people on display, purposely to evoke either tears of pity or impatient contempt.

You also can hear it in the angry screeds of political pundits, both liberal and conservative, who seem forever apoplectic because American democracy moves too slow, or does not reflect their own “common sense” ideas.

Listen close to anyone on social media or cable news channel shows who contemptuously interrupt each other because what they have to say is plainly right and much more important.

Whenever you see a person – or a work of art – that has no ironic sense of itself or its message, it becomes a frightening experience, a warning to our own natural penchants for playing the innocent.

We’ve misread the central metaphor of a great American novel. We have gotten carried away by its lyricism of innocence.

As 10-year-old Phoebe reminds her angst-ridden teenage brother, he misunderstood the metaphor of Robert Burns’ poem: Holden replaced Burns’ “Gin a body meet a body,” with “When a body catch a body.”

As Salinger aficionado Kenneth Slawenski points out in his fine biography: “To ‘catch’ children from falling into the perils of adulthood is to intervene by rescuing, preventing, or forbidding. But to ‘meet’ is to support and share, which is a connection.”

It’s all so terribly prescient and contemporary.

As adults, we should know better. We know how messy and complex life can be.

We also know we’re an integral part of that messiness, wrestling with demons both self- and society-made.

Several generations have read Catcher in the Rye the way Holden would have wanted us to read it – as if he’d written it.

But J.D. Salinger wrote it.

It’s time to read it like an adult.